Characteristically, it was Naples itself and its apparent timelessness that most drew Hazzard: “If Virgil were to sail one day into the Bay of Naples, he would recognize it,” she once remarked. The definitive moment of her early life was her decision, seemingly on a whim, to leave New York for Naples and her career progression - her Leopardi-inspired Italian being enough to get her a year-long posting there from the UN when American life had begun to sour following further disappointments in love. Vedeniapine was a White Russian of high principle and “evident knowledge,” and the teenage Hazzard, on having to leave their furtive romance behind when her sister Valerie became gravely unwell, suffered operatic heartbreak. Equally formatively, she met Alec Vedeniapine there, the first great love of her life and later the inspiration for the sweeping melodrama The Great Fire, published more than fifty years after he ended their (unconsummated) relationship. Hong Kong had once offered Hazzard her first glance at cosmopolitanism, the family having followed the diplomat Reg overseas immediately after World War Two. Were it not for this, and Hazzard’s realization that “I would have to rescue myself,” she might have continued to work in offices such as those in which she found employment at the UN in New York, having previously dabbled in a little “rudimentary intelligence” as a teenager in Hong Kong. In her case, a love of Giacomo Leopardi’s poetry seduced her into learning Italian in order to read him in the original.

Auden himself that poetry can make something happen. Hazzard’s own life, especially in its early, striving years, would involve regular attempts to traverse seemingly impossible divides. Her parents were both British imports, Welsh Reg and Scottish Kit, who met while working on the construction of Sydney Harbor Bridge. This first biography, by Brigitta Olubas, an academic who has already written a monograph on Hazzard and edited her collected short stories, gives us a portrait of the self-created artist throwing off the “suffocating gentility” of postwar life in her native Australia, its “tyranny of distance” from what she saw as the swim of things, the permanent elsewhere, and seeking a life of books and worldly high culture.

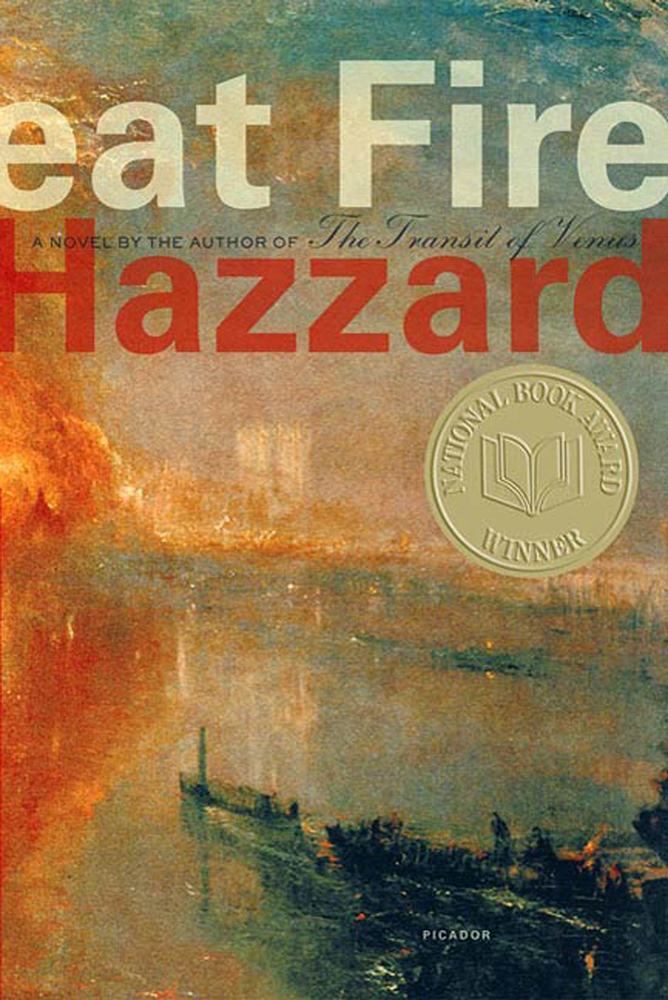

She came to represent “a vanished age of civility”: there is something Victorian about her novels, despite the last of them, The Great Fire, being published in 2003, by which time she was starting to resemble “an exotic bird blown off course.” Shirley Hazzard’s “untimeliness” is a recurrent aspect in most descriptions of her, both the writing and the person.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)